Britain’s Reindustrial Revolution

Reindustrialising Britain: Building a modern, resilient manufacturing ecosystem beyond high-tech headlines.

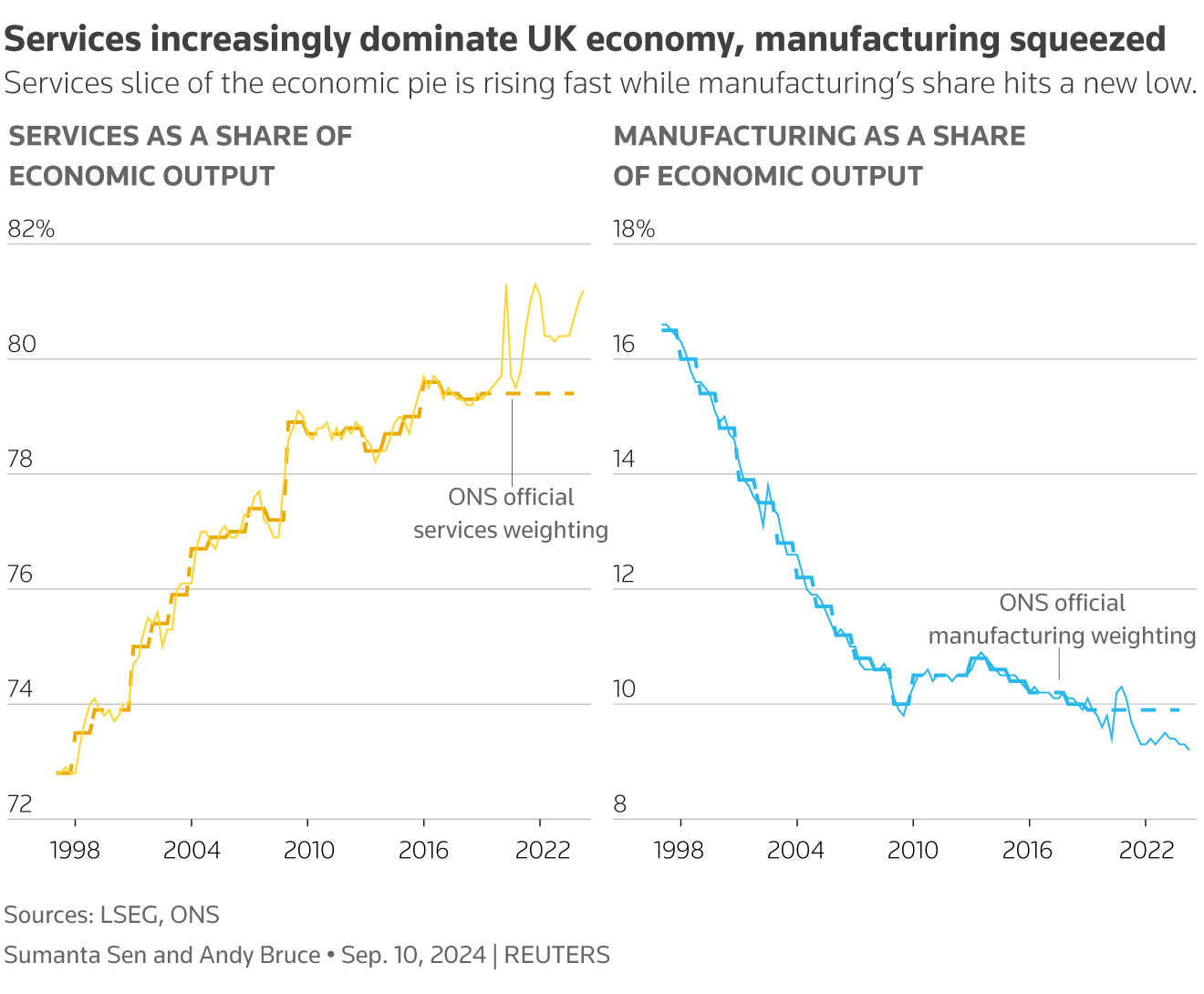

For decades, the gradual erosion of Britain’s manufacturing base through offshoring went largely unnoticed. Goods became cheaper even as domestic production declined, and cleaner air seemed like an added benefit. Services surged to dominate the economy, reshaping the nation’s industrial identity.

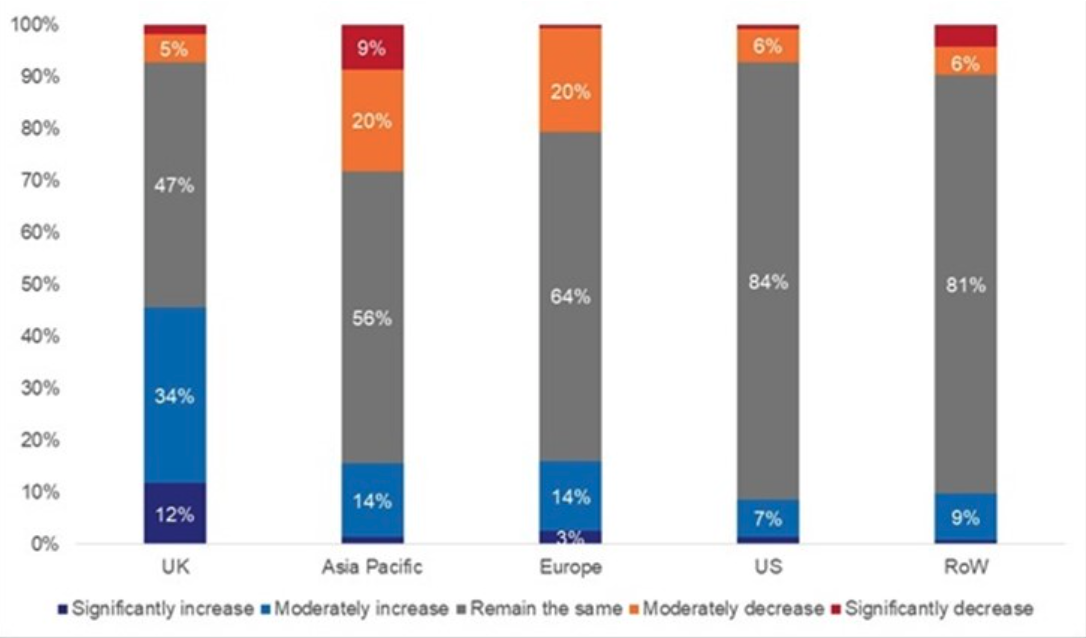

COVID-19 proved to be a reckoning moment (in more ways than one). It exposed the fragility of global supply chains on which we had come to depend. Timber prices increased by 50%, cement rose by 30%, and the UK faced critical shortages of medical essentials, from PPE to antibiotics like gentamicin API. Suddenly, our reliance on foreign manufacturing looked less like economic efficiency and more like strategic vulnerability. This realisation sparked a shift in mindset across the country. A 2020 survey by Make UK and Oracle showcases this change in sentiment. In 2020, more than a third of manufacturers said they wanted to increase their use of UK-based suppliers, with 12% planning significant onshoring.

That sentiment has only gained urgency in light of last month’s threat of British Steel’s blast furnaces in Scunthorpe shutting down. If realized, it would have ended primary steel production in the UK, making it the only G7 nation without this critical capability. The issue has pushed industrial sovereignty to the forefront of public and political debate.

Throughout government, industry, and media, there is a growing call to ‘reindustrialise’ Britain in Scunthorpe and beyond. The 2,700 jobs at risk in Scunthorpe are significant and merit urgent attention. But the increasingly loud demand for reindustrialisation on both sides of the aisle addresses something more foundational: Brits are growing uneasy about the erosion of industrial sovereignty. And in an AI-driven future where cognitive tasks face increasing automation, the value of physical production becomes even more critical.

What British Reindustrialisation Really Means

Reindustrialisation isn’t a nostalgic call to resurrect the past. It’s about building a modern, resilient, high-value manufacturing ecosystem. Rather than bringing everything back, countries are looking for ways to rebuild strategic industrial sectors and understand what it takes to sustain them long-term.

The UK government is due to publish its Industrial Strategy White Paper in the coming months, outlining its vision for modern manufacturing revival. Already, £4.5Bn in investment has been pledged across four key sectors:

- Automotive: Over £2 billion to support vehicle development, manufacturing, and supply chains.

- Aerospace: £925 million to foster advanced aircraft technologies.

- Life Sciences: £520 million to enhance biotech and pharma innovation.

- Green Industries: £960 million to develop clean energy manufacturing capabilities.

These are undeniably essential areas. Two of them already rank among the UK’s strongest industrial ecosystems. Britain's aerospace industry is the second-largest in the world, only lagging behind the United States. It generates £30.5 billion in annual turnover and, with 70% of production exported, it is a major contributor to national trade. Similarly, life sciences is a long-established area of excellence, contributing £46.7 billion annually through a thriving ecosystem of pharmaceutical companies, universities, and deep-tech startups.

Focus is necessary, especially when the objective is as ambitious and expansive as reindustrialisation. That said, these four sectors are only the starting point. To make these efforts successful, and achieve the broader goal of greater industrial resilience, we must consider two often-overlooked elements: the supply chains that sustain them, and the foundational industries that underpin everyday resilience.

First, sectors require a sophisticated understanding and investment in underlying supply chains. As we know, no sector operates in isolation. Every strategic industry relies on upstream materials and infrastructure. Take automotive, for example. Most modern cars are made up of between 20,000 and 30,000 individual parts including fasteners, semiconductors, and batteries. If the UK wants to lead in electric vehicle production, it must invest in car designs and assembly lines but also secure sustainable supply of these critical inputs.

Second, we must broaden our view of what manufacturing resilience really means. Industrial prowess is not just about high-tech or export-led industries. A sovereign economy must be able to meet its most basic needs—food, shelter, and mobility—independently. Foundational sectors like food and beverage manufacturing, agricultural production, construction materials (cement, steel, insulation), and logistics and packaging all underpin a strong, resilient economy. These industries are vital to the daily functioning of a country, yet are often overlooked in policy narratives.

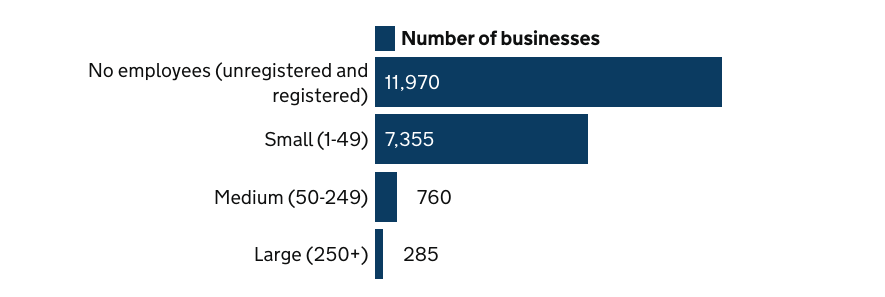

This is especially important considering these sectors are rich with mid-market manufacturers—businesses typically employing fewer than 250 people, deeply rooted in their regions and central to the UK economic fabric. While industries like life sciences and aerospace are led by national champions—AstraZeneca, GSK, BAE Systems—sectors like food and beverage are held up by thousands of small, frequently family-run, businesses. Supporting these companies strengthens local economics and rebuilds communities hit hardest by offshoring.

Number of UK food and drink manufacturers by business size, 2024

Source: Business Population Estimates (BPE), DBT

Rethinking Manufacturing for the Next Era

We are entering an exciting decade of industrial revitalisation in the UK, one that offers a rare chance to rethink what manufacturing can look like. Reindustrialisation is not just about recreating the past. It’s about building something smarter, more future-proof, and something that can rival our services sector which has become the bedrock of the UK economy.

In sectors where the UK seeks to maintain global leadership — such as aerospace and life sciences — we should ask ourselves bold questions that go beyond the status quo. A recent piece from Techpolitik titled Meta-Production challenges us to imagine a more expansive, even sci-fi, vision for Western manufacturing if we embrace modularity, AI-native systems, and new physical workflows. It’s a provocation worth taking seriously, especially with over £4.5 billion dedicated to reindustrialization.

At the same time, in the foundational sectors of our economy—food and beverage, construction, logistics — where thousands of mid-market businesses quietly power the UK industrial base, the opportunity is less headline-grabbing yet just as important. The challenge here is to modernise operations: reduce waste, increase output, and lift margins so that these firms can continue to thrive and serve as the essential building blocks of our manufacturing ecosystem.

At Ferry, we work with both manufacturers rethinking production from the ground-up and those making steady, incremental improvements to existing operations. Both are equally exciting and necessary for reindustrialisation. The future of British manufacturing won’t be shaped by a single sector or approach but by the collective ambition of thousands of business owners, policymakers, operational leaders, technology founders, and researchers. As the saying goes, it takes a village.